Patient Zero

Gaetan Dugas

By: Tan Sri Son | 29/08/2025

Gaëtan Dugas: The Misunderstood “Patient Zero” of the AIDS Epidemic

In the history of medicine, few figures have been as unfairly stigmatized as Gaëtan Dugas, a Canadian flight attendant once labeled the “Patient Zero” of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in North America. For years, his name became synonymous with the supposed origin of one of the deadliest pandemics in modern history. Yet, decades later, scientific research would reveal that Dugas was not the man who brought HIV to North America, but rather one of its early victims. His story is both a tragic misunderstanding and a lesson about how fear and misinformation can shape history.

The Early Days of an Unknown Disease

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, doctors in cities such as Los Angeles, San Francisco, and New York began noticing a disturbing pattern. Young, otherwise healthy men were being admitted to hospitals with rare illnesses: aggressive forms of Kaposi’s sarcoma, a cancer usually found in older men, and opportunistic infections like Pneumocystis pneumonia, which typically affected people with severely compromised immune systems.

At first, these cases seemed isolated. But by 1981, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) had documented clusters of similar patients. What made the situation even more alarming was that the affected men were predominantly gay, which led the illness to be initially called GRID (Gay-Related Immune Deficiency) before it was officially named AIDS (Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome) in 1982.

The Search for a Pattern

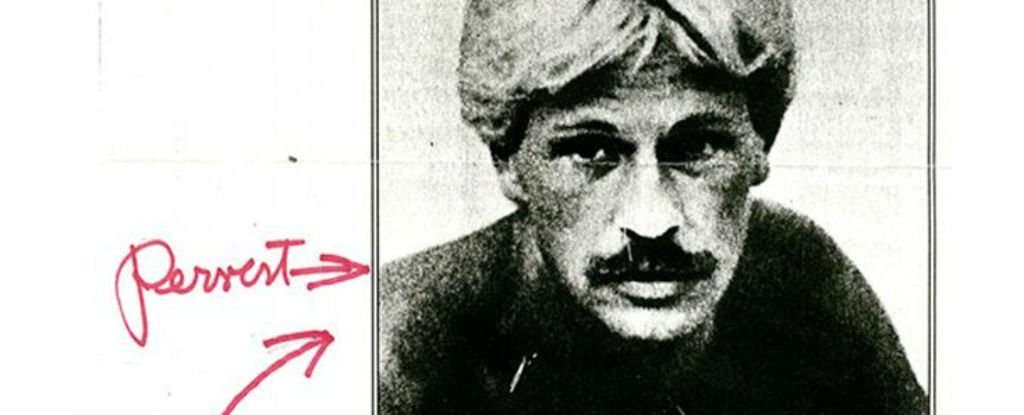

As the epidemic spread, epidemiologists began investigating how the disease was transmitted. Dr. William Darrow and his team at the CDC mapped sexual connections between patients and noticed a chain of infections that appeared to converge on one individual: a handsome, charismatic, 31-year-old Air Canada flight attendant named Gaëtan Dugas.

Dugas was open about his sexuality, had numerous partners across North America, and because of his job, he traveled frequently between cities such as Los Angeles, San Francisco, New York, and Montreal. To researchers, he seemed to be the common thread. In their records, he was labeled as “Patient O”, meaning “Outside California.” But in a fateful twist of history, the “O” was misread as a zero. Over time, “Patient O” became “Patient 0,” and the myth was born: Gaëtan Dugas was the man who brought AIDS to America.

The Making of a Scapegoat

In 1987, journalist Randy Shilts published And the Band Played On, a groundbreaking book documenting the early years of the AIDS crisis. While the book exposed government inaction, social prejudice, and the suffering of patients, it also highlighted Dugas as “Patient Zero.” Shilts portrayed him as a reckless figure who, even after learning he carried the disease, continued to have unprotected sex and told partners defiantly, “I’ve got it, and I’m going to give it to you.”

The media seized on this image, turning Dugas into a symbol of irresponsibility and danger. Headlines sensationalized his role, painting him as the man who single-handedly ignited the epidemic in North America. To a fearful and stigmatizing society, the idea of a single person being responsible for the outbreak provided a convenient scapegoat.

The Reality: Science Clears His Name

For decades, the myth of Gaëtan Dugas as Patient Zero persisted. But in 2016, a team of scientists led by Dr. Michael Worobey of the University of Arizona revisited the question using advanced genetic techniques. They analyzed preserved blood samples from HIV-positive patients dating back to the 1970s, years before Dugas’s name appeared in medical records.

The results were clear: HIV was present in New York City by at least 1971, and possibly even earlier. The virus had likely spread from Central Africa to the Caribbean, and from there into the United States. By the time Dugas was sexually active in North America, HIV was already deeply entrenched in multiple cities.

The genetic evidence showed conclusively that Gaëtan Dugas was not the origin of the epidemic. Instead, he was one of many thousands who contracted HIV during its early spread. Far from being a villain, he was a victim.

A Life Overshadowed by Myth

Lost in the shadow of the Patient Zero narrative was the reality of Gaëtan Dugas’s life. Born in Quebec in 1953, he was described by friends as charming, flamboyant, and unapologetically open about his sexuality at a time when being openly gay was still socially risky. His job as a flight attendant allowed him to travel widely, and he embraced the freedom that came with it.

But when the first symptoms of illness appeared, Dugas faced the same fear, stigma, and suffering as others. He died in 1984 at the age of just 31, never knowing that he would be immortalized as a central—though mistaken—figure in the history of AIDS.

Lessons from the Patient Zero Myth

The story of Gaëtan Dugas is not just about one man but about how societies respond to disease. The Patient Zero myth reflected a deep need to assign blame during a time of panic and uncertainty. By focusing on an individual, people avoided confronting the larger truths:

That HIV had been spreading silently for years.

That governments were slow to respond to the crisis.

That stigma against gay men worsened the suffering of countless victims.

Today, epidemiologists are far more cautious when using the term “patient zero.” The idea of a single identifiable origin is often misleading. In global pandemics, diseases spread through networks, communities, and movements of people—not through a single individual.

Conclusion

Gaëtan Dugas’s story is one of misunderstanding and tragedy. Wrongly cast as the villain who brought HIV to America, he became a symbol of fear and stigma in the early years of AIDS. Yet, modern science has cleared his name, proving that the epidemic had already taken root in North America long before he was infected.

His case remains a powerful reminder of the dangers of scapegoating in times of crisis. Behind the sensational headlines was not a monster, but a young man who suffered and died like so many others during one of the most devastating epidemics in history. In remembering him, we are reminded to seek truth, compassion, and understanding in the face of disease—qualities that remain as essential today as they were in the early days of AIDS.

Coming Soon

We're on a mission ..........................

Discover our full library of The Theos e-magazines and articles — all completely free to read.

We are a crowdfunded publication, dedicated to sharing knowledge, reflection, and theology with readers around the world.

Your support and donations help us continue offering open, accessible content for everyone, everywhere.

Join us in keeping wisdom free.

@ the theos since 2023 © 2023. All rights reserved.